Loggerhead Key, 250 by 1,200 m (820 by 3,940 ft) in size, with an area of 260,000 m2 (64 acres) is the largest. This island has the highest elevation in the Dry Tortugas, at 10 feet (3.0 m). The Dry Tortugas lighthouse, 46 m (151 ft) 46 meters high, is on this island.

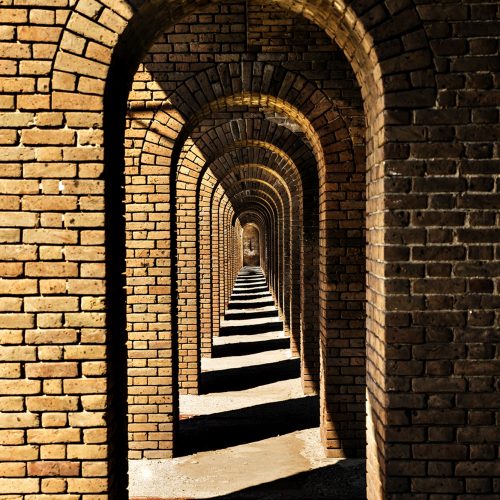

Garden Key, with Fort Jefferson and the historic Tortugas Harbor Light (20 m (66 ft)). It is 4 km (2.5 mi) east of Loggerhead Key. Garden Key is the second largest island in the chain, at 400 by 500 m (1,300 by 1,600 ft) in size, with an area of 170,000 m2 (42 acres). The original size, before construction of Fort Jefferson, has been estimated at 30,350 to 35,610 m2 (7.50 to 8.80 acres).

Bush Key, formerly named Hog Island because of the hogs that were raised there to provide fresh meat for the prisoners at Fort Jefferson, just a few meters east of Garden Key. At times, Bush Key is connected to Garden Key by a sandbar. The island is the third largest, 150 by 900 m (490 by 2,950 ft), area 120,000 m2 (30 acres), less than 1 m (3 ft 3 in) high. Bush Key is the site of a large tern rookery. It is closed to visitors from April to September to protect nesting sooty terns and brown noddies.

Long Key, 59 m (194 ft) south of the eastern end of Bush Key, 50 by 200 m (160 by 660 ft) in size, area of 8,000 m2 (2.0 acres).

Hospital Key, so called because a hospital for the sick of Fort Jefferson had been built there in the 1870s. The island was formerly called Middle Key or Sand Key. It lies 2.5 km (1.6 mi) northeast of Garden Key and Bush Key, 70 m (230 ft), area 4,000 m2 (0.99 acres), and is 1 m (3 ft 3 in)high at its highest point.

Middle Key, 2.5 km (1.6 mi) east of Hospital key, 90 m (300 ft), area 6,000 m2 (1.5 acres), due to various seasonal changes, storm patterns and tidal cycles it is not always above sea level, disappearing for weeks or months only to reappear again.

East Key, 2 km (1.2 mi) east of Middle Key, 100 by 200 m (330 by 660 ft), area 16,000 m2 (4.0 acres), over 2 meters high.

The three westernmost keys, which are also the three largest keys (Loggerhead Key, Garden Key, and Bush Key), make up about 93 percent of the total land area of the group.