The British steamer, Lugano, from Liverpool, was headed for Havana with general cargo that included fine silks, wines, rice, and other foods valued at $1 million. She was also carrying 116 passengers, including 12 women and children. All of the passengers except 2 were Spanish immigrants en route to Cuba.

On March 9, 1913 in high winds and heavy seas and significantly off course, Captain P. Penwill grounded on Long Reef. The tug Rescue was radioed, and safely took the passengers of Lugano to Key West while the Captain and crew remained aboard. Cargo was removed, and the hold was intentionally flooded to prevent further pounding on the rocks. By March 20th, seven large loads of cargo had been removed and taken to Key West. Wreckers were busily pumping water out of Lugano so that her boilers could be re-lit, allowing her own pumps to dewater the hull. By March 22nd, their efforts succeeded, but even with the ship’s pumps working night and day, the ill-fated vessel was still lodged on the reef and listing heavily to port. On March 27th, The Miami Herald reported there were over 75 wrecking boats attempting to save the cargo. The ensuing confusion and foul weather made it easy for unscrupulous salvors to slip away and stash cargo on nearby reefs. Much cargo was stolen by the Key West wreckers of Dr. Lykes, including linens and 350 cases of brandy. Rumors of the thefts prompted U.S. Customs to dispatch officials to monitor the wreck.

By April 4th, the crew had abandoned Lugano, which was again full of water. The Lee Brothers, wreckers from Miami, were later contracted to deliver the ship to Key West for $17,000.00. The estimated value of the saved cargo was $150,000.00. Lugano was three stories deep below the water line and was the largest boat to ever go on the rocks of the Florida reefs up to that time.

All efforts to refloat Lugano were abandoned on April 15th. Two days of high winds pounded the already battered vessel until it was considered a total loss. Wreckers removed nearly everything, leaving only the hull. A settlement on May 28, 1914, gave the primary salvors $64,126.67, the secondary salvors $14,084.30, and the remaining salvors $2,228.18. The schooner Dr. Lykes’ share was forfeited because of discrepancies between cargo collected and cargo delivered.

In February, 1917, the yacht Ada M struck Lugano, which was the first report of a ship hitting this wreck. A warning to mariners was issued on January 13, 1920 stating that the wreck of Lugano was a danger to navigation. The wreck was estimated to be 3000 tons and had a broken mast and stack visible under water.

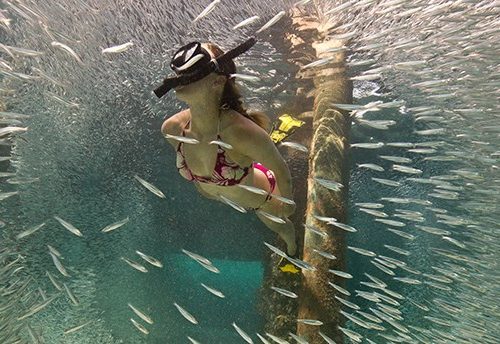

Lugano now lies 25 feet underwater on Long Reef in Biscayne National Park.